Notes:

The Soviet Union sought to address the imbalance in nuclear weaponry by installing such weapons in Cuba. According to Richard Reeves writing in President Kennedy, the United States had approximately five thousand deliverable nuclear weapons. U.S. intelligence estimated that the Soviets had three hundred deliverable weapons. The U.S. estimate of the number of Soviet intercontinental missiles targeted at the United States was now seventy-five. Those missiles had relatively primitive guidance systems, and analysts on both sides doubted they cold even come close to their presumed targets. The Soviets also had ninety-seven short-range missiles on submarines that had to surface before they could launch, and 155 heavy bombers.

The U.S. had 156 ICBMs, 144 Polaris missiles that could be fired from submarines without surfacing, and 1,300 bombers all nuclear-armed and a third of them in the air at all times.

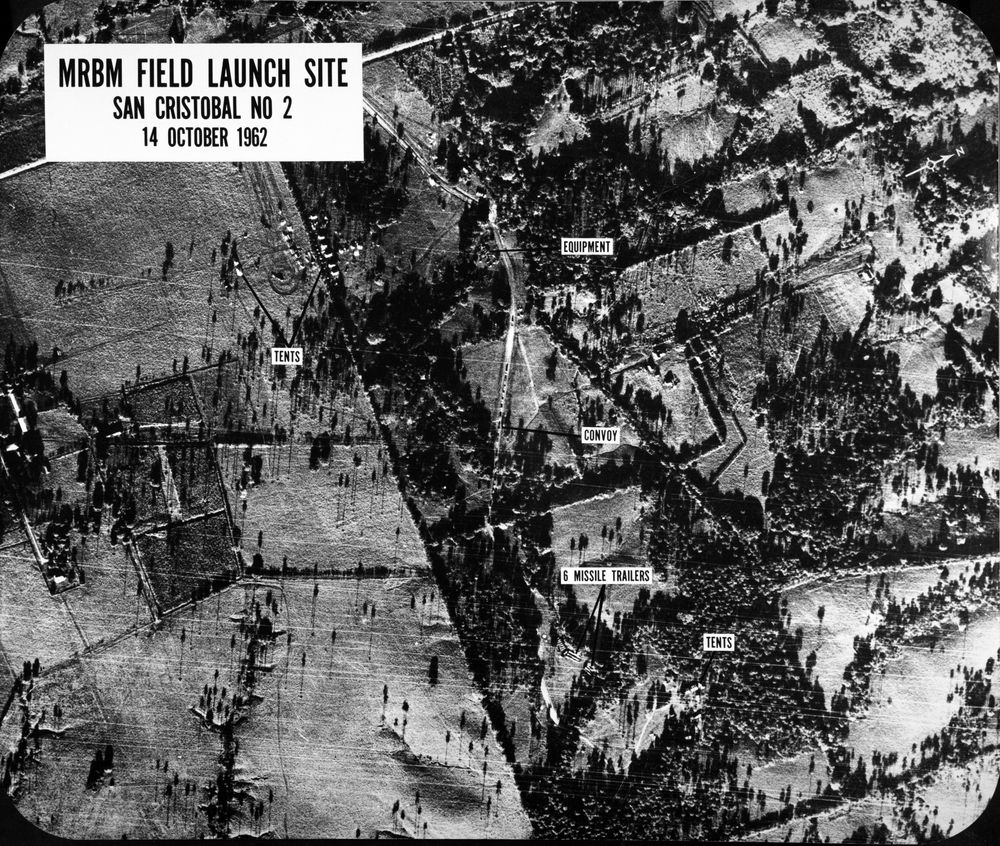

The USSR successfully delivered a large nuclear arsenal to Cuba before the quarantine went into effect: 36 R-12 MRBMs and their warheads; 24 warheads for R-14 IRBMs (these missiles were not delivered due to the quarantine); 80 2-20 kiloton warheads for winged rockets (cruise missiles); 12 2-kiloton warheads for tactical artillery for attacking invaders; 6 warheads for surface to sea missiles; and 6 8-12 kiloton bombers for the 6 IL-28 bombers that had been delivered in crates.

In addition, they had deployed an air defense system of SAMs capable of striking aircraft at 70,000 feet. They also had 40 MiG-21 and 6 MiG-15 fighter aircraft, as well as helicopters, gunboats, tanks and artillery. (Sherwin, 200)

Pages on this site describing events of the Cuban Missile Crises are based primarily on: Serhii Plokhii, Nuclear Folly: A History of the Cuban Missile Crisis, W. W. Norton & Company, New York. 2021.

1 Robert F. Kennedy, Thirteen Days W. W. Norton & Company, New York, 1971. p.19.

2 Richard Reeves, President Kennedy: Profile in Power, Simon & Schuster, New York. 1993. p. 223

3Ibid., p. 372

4 Martin J. Sherwin, Gambling with Armageddon, Alfred A. Knopf, New York. 2020. pp. 241-2

5 Reeves, p. 392.

6 Reeves, p. 398.

Photo Credits:

Photo of MRBM Field Launch Site San Cristobal 14 October 1962. United States Department of Defense Cuban Missile Crisis Briefing materials. John F.Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston. Public Domain.

Photo of MRBM Field Launch Site San Cristobal 23 October 1962. United States Department of Defense Cuban Missile Crisis Briefing materials. John F.Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston. Public Domain.