Frost prepared for his magnificent career, less through formal schooling and more so by reading and listening. In his letter to John Bartlett of July 4, 1913, Frost wrote:

“I alone of English writers have consciously set myself to make music out of what I may call the sound of sense. Now it is possible to have sense without the sound of sense (as in much prose that is supposed to pass muster but makes very dull reading) and the sound of sense without sense (as in Alice in Wonderland which makes anything but dull reading). The best place to get the abstract sound of sense is from voices behind a door that cuts off the words.

The sound of sense, then. You get that. It is the abstract vitality of our speech. It is pure sound–pure form. One who concerns himself with it more than the subject is an artist. But remember we are still talking merely of the raw material of poetry. An ear and an appetite for these sounds of sense is the first qualification of a writer, be it of prose or verse.” 1

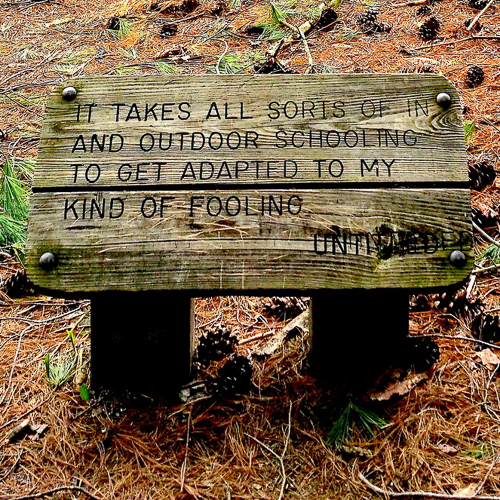

Sign at Robert Frost Interpretive Trail

Sign at Robert Frost Interpretive TrailSomewhat later, Frost expanded on his way of making poetry and how it came to him. In conversation, following publication of his first poem —

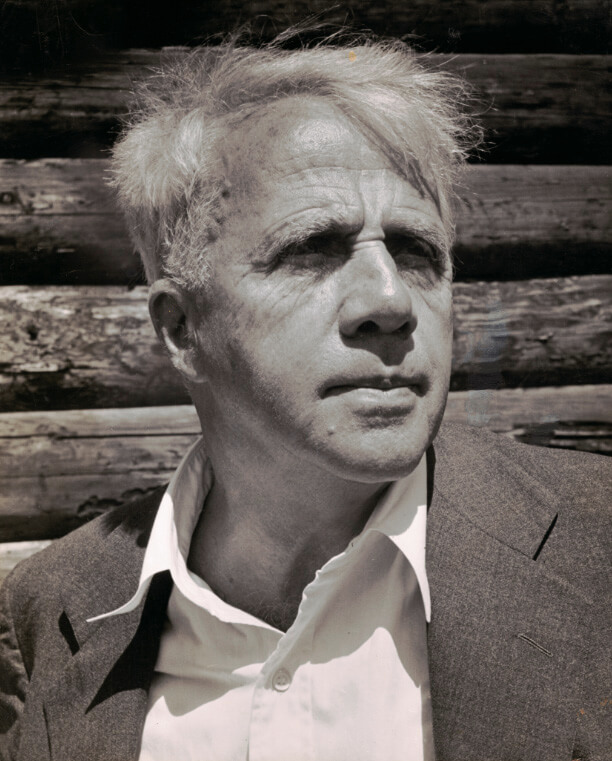

Frost at his Ripton Cabin ca 1941

Frost at his Ripton Cabin ca 1941“Something providential was happening to me. I’m sure the old gentleman didn’t have the slightest idea he was having any effect on a very stubborn youngster who thought he knew what he knew. But something he said actually changed the whole course of my writing. It all became purposeful.

One day as we talked he said to me that when he read my poems it was just like hearing me talk. I didn’t know until then what it was I was after. When he said that to me it all became clear. I was after poetry that talked. If my poems were talking poems – if to read one of them you heard a voice – that would be to my liking! … Whenever I write a line it is because that line has already been spoken clearly by a voice within my mind, an audible voice.”

With regard to form, Frost was definitive:

“Because I have been, what some might call, careless about the so-called proper beat and rhythm of my lines, there have been those who think I write free verse. Now, I am not dead set against vers libre; but you know there is no idea you cannot express beautifully and satisfactorily in the iambic pentameter. Much of my verse is written in this form – blank, unrimed verse. I have always maintained that it takes form to properly perform and free verse has no form, and so its performance is meager … The greatest freedom poetry can attain is having form, a frame to work in. Free verse is batting a ball into space and wondering why it doesn’t return to the batter. Poetry written in form is like batting a ball against the side of a wall and feeling it return to the bat. A picture frame with its four simple lines is necessary to the showing of a picture. Try it and see. The frame thus becomes a part, even, of the picture.” 2

IN OUR COMPANION TEXT, Paul Dimond and Roger Mills write that Frost “studied Latin and then turned to Greek; he read the English writers and poets of the past and of his day. He was as well read as any literature professor. He also explored the learning and scientific theories of James, Dewey, Bohr, Einstein, and Planck, to name only a few of the many he studied and remarked on… [Frost] joined the faculty of Amherst College in 1917. In 1919, he wrote about his emerging philosophy of creating, writing, and learning, using a metaphor from his farming days:3

A man who makes really good literature is like a fellow who goes into the fields to pull carrots. He keeps on pulling them patiently enough until he finds a carrot that suggests something else to him. It is not shaped like other carrots. He takes out his knife and notches it here and there, until the two pronged roots become legs and the carrot takes on something of the semblance of a man. The real genius takes hold of that bit of life which is suggestive to him and gives it form. But the man who is merely a realist, and not a genius, will leave the carrot just as he finds it. 4

Notes:

1 Robert Frost, Donald Sheehy, Mark Richardson and Robert Faggen, The Letters of Robert Frost Volume I 1886-1921.The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2014.

2 Peter J. Stanlis. Robert Frost — The Poet as Philosopher. ISI Books, Wilmington, Delaware. 2007. xiii – xv. Material first appeared in Louis Mertins, Robert Frost: Life and Talks-Walking, 1965 pp 197-98.

3 Paul Dimon and Roger Mills, “Robert Frost: The Poet as Educator,” JFK: The Last Speech, 2018, 37-42.

4 Robert Frost. Remarks on Form in Poetry. In: Mark Richardson, ed. The Collected Prose of Robert Frost. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. Cambridge. (First Harvard University Press paperback edition, p. 79).

Photo Credits:

Sign at Robert Frost Interpretive Trail: Judy Bicknell photo

Frost at his Ripton Cabin ca 1941: Courtesy of Dartmouth College Library, used with the permission of the Estate of Robert Frost

Bibliography:

In addition to the publications footnoted above, reference has been made to the following:

Robert Frost, Donald Sheehy, Mark Richardson, Robert Bernard Hass and Henry Atmore, The Letters of Robert Frost Volume II 1920-1928. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2016.

Jay Parini, Robert Frost A Life. Henry Holt and Company, 1999.

Mark Richardson, The Collected Prose of Robert Frost. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2007.