In 1962, Frost accompanied Stewart Udall, Secretary of the Interior, on a visit to the Soviet Union. Despite not feeling well, Frost agreed to “make the trip if the President wanted him to go.” As Udall reflected in his 1972 article, “Robert Frost’s Last Adventure,”

Frost went because he felt he could make a contribution to peace if given the opportunity to talk man to man with Khrushchev. His determination was fierce. Several times during the long flight to Moscow he asked the piercing question, “Will we get to see him?” I was dismayed that he had his heart set on “the big conversation,” and when I told him the odds were heavily against either of us seeing the Soviet leader, he became downcast. Later his frustration deepened, and in the middle of a listless poetry reading in Moscow, he growled at Franklin Reeve, his American interpreter, “What the hell am I going to do here anyway if I don’t get to see Khrushchev?” Frost took pride in his ability to put himself in anther man’s shoes, and it was obvious he had not only gone to great lengths to understand Khrushchev’s situation, but in the process he had also developed a perspective of cold-war competition that was generous in its estimate of the potential of Soviet society. This was not a difficult exercise for Frost. In 1959, when some students asked him about Boris Pasternak’s troubles with the Soviet hierarchy, he replied sharply, “Pasternak is a brave man. He wants to be a Russian and we’re going to get him killed if we keep trying to use him against Russia.” And at a press conference much later he made this sympathetic observation about chairman Khrushchev: “Think of his fears — of us in front of him, of what’s around him, of the Politburo behind him.”

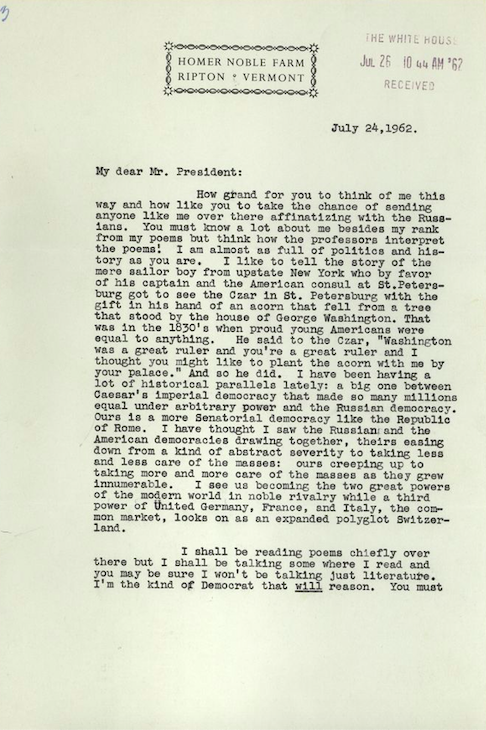

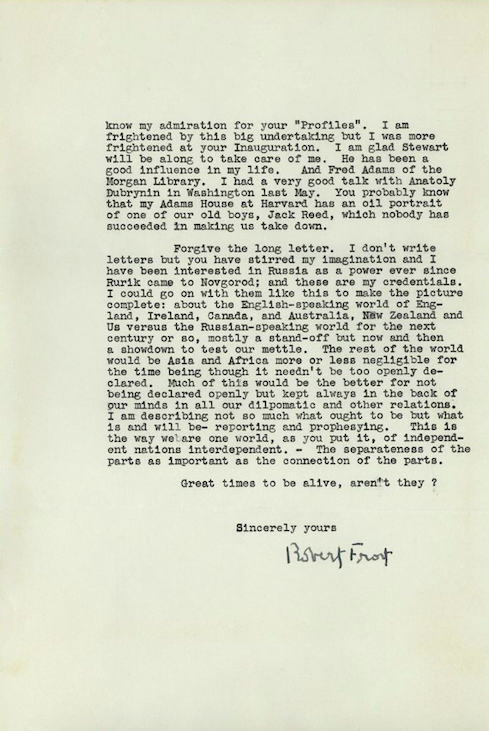

Now, however, it was not fears, but hopes, which Frost wanted to explore. As he surveyed the sweep of history, Frost became convinced that human survival depended on the gradual social and political convergence of the two systems. In the acceptance letter he wrote to President Kennedy about his Russian trip, he said he would be “reporting and prophesying,” and he outlined his convergence concept in these words: “I have thought I saw the Russian and American democracies drawing together, theirs easing down from a kind of abstract severity to taking less and less care of the masses; ours creeping up to taking more and more of care of the masses as they grow innumerable.”

Frost told me that he was prepared to say this, and more, “straight out” to Khrushchev, that he wanted to tell the Russian leader “to his face” that he considered him a courageous leader and admired his humanizing reforms. He had prepared his appeal with the care and craft he gave to the writing of poetry, and I could see he was ready to speak as an emissary of mankind, not only for the people of the United States. He recalled that Aristotle had summed up the Greek experience by concluding that great nations at the pinnacle of power prevail only when they behave greatly. Frost wanted passionately to discuss with Khrushchev a hundred years of grand rivalry based on an Aristotelian code of conduct he called “mutual magnanimity.” Frost loathed Khrushchev’s “coexistence” slogan, but it was clear he planned to conceal his distaste for it as he presented his own plan. To him “coexistence” implied a sterile, negative view of the human prospect, as against the kind of context for excellence that he thought might serve as more equivalent for war and poisonous propaganda.

Frost and Udall each did meet with Khrushchev. Unbeknownst to them, and as Udall later surmised, the Soviets were preparing missile launching sites in Cuba, and “Khrushchev needed to send [Kennedy] tidings of his sanity, to prove he was still in charge.” He wanted to keep Washington guessing, by being alternately peaceful and tough.

Frost spoke his concerns to Khrushchev: the two nations should engage in a “noble rivalry” in sports, science, art and democracy; they should have a code of conduct; and the leaders should be high-minded, encouraging contests for excellence. “Leaders had a moral duty not only to steer clear of senseless wars but also to create a climate hospitable to wide-ranging contact and competition. If there was restraint, if the limits of national power were recognized, both sides would soon realize that ‘petty squabbles and blackguarding propaganda’ had to be avoided. As Frost put it, ’Great nations admire each other and don’t take pleasure in belittling each other.’” 2