Notes:

1 Joseph Campbell with Bill Moyers, The Power of Myth, Anchor Books. New York, 1991.

2 Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., Robert Kennedy and His Times, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, 1978. p 14.

3 Mark Mooney and Russell Goldman, “Ted Kennedy Was Surrounded by Crying, Praying Family,” ABC News. Aug. 26, 2009. (Reporting on the death of Senator Ted Kennedy and recalling his mother, Rose Kennedy’s motto.

4 Robert Dallek, An Unfinished Life John F Kennedy 1917-1963, Little, Brown and Company. New York, 2003. pp 39-40.

5 Papers of John F. Kennedy. Personal Papers. Early Years, 1928-1940. Choate yearbook, 1935

5 Joseph P. Kennedy to John F. Kennedy 9/10/40 Box 4A, Personal Papers. John F. Kennedy Library and Museum.

6 Quotes in this section as well as general reference to facts and events are from Robert Dallek, An Unfinished Life John F Kennedy 1917-1963, pp 42-67. Specific references to p 53 and p 56.

7 Ibid p 57, p 59.

8 Ibid p 55, p 67.

9 According to Mayo Clinic, “in Addison’s disease the adrenal glands produce too little cortisol and often insufficient levels of aldosterone as well.” Symptoms known to have afflicted Kennedy, the inability to gain weight, abdominal pain and others symptoms are listed on the Mayo Clinic website. Mayo Clinic website: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/addisons-disease/symptoms-causes/syc-20350293

10 Robert Dallek, An Unfinished Life John F Kennedy 1917-1963, Little, Brown and Company. New York, 2003. pp 153-4.

- In 1934, while a junior at Choate, he was treated for lucopenia, a deficit of white blood cells causing increased risk of infections. Later, having suffered constant intestinal problems and an inability to gain weight, he spent a month at Mayo Clinic, where he underwent numerous repeated and unpleasant tests. The diagnosis of duodenitis, spastic colitis and intestinal and colonic inflammations required finding a better diet and relieving emotional stress but did not provide a solution.

- In 1935, illness forced his return from Europe. Recuperation led to late enrollment at Princeton, then recurring illness caused him to withdrew in December. He spent the next two months at a Boston hospital.

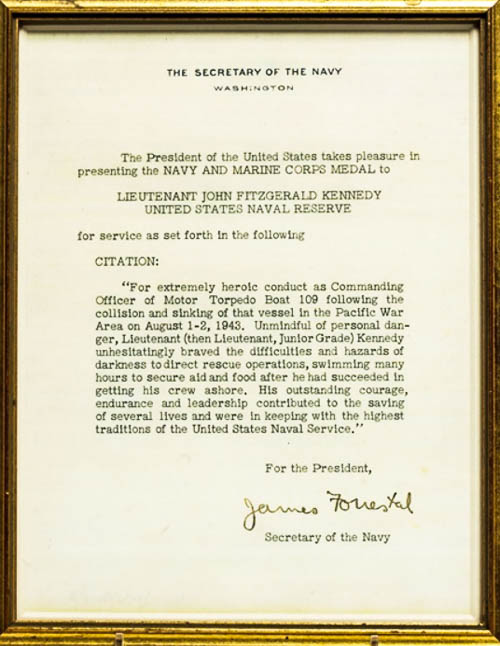

- 1936 enrollment at Harvard and participated in football and swimming. 1936-37 were years of relatively good health.

- Feb 1938 saw more tests at Mayo Clinic, a stay in the Harvard infirmary, 4 weeks at New England Baptist Hospital.

- Feb 1939 more tests at Mayo Clinic.

- During 1940, onset of back pain and tests at Mayo Clinic.

- December 1943 the Navy ordered Kennedy to return to Rhode Island for medical treatment

- Jan 1944 at Mayo Clinic

- Feb 1944 New England Baptist Hospital recommended back surgery

- June 1944 Chelsea Naval hospital diagnosed a ruptured disk; operated on at New England Hospital. Soft cartilage was removed

- In 1947 while traveling abroad, Addison’s disease was diagnosed; gravely ill upon return to the U.S. and given the last rites of the Catholic Church.11

11 Ibid p 78ff.

12 Jon Meacham, The Soul of America The Battle for Our Better Angels, Random House. New York. 2018 p 149.

13 Remarks of John F. Kennedy at an Induction Ceremony for Navy Recruits, Charleston, South Carolina, July 4, 1942. The Full text may be found at: See the full text https://www.jfklibrary.org/Research/Research-Aids/JFK-Speeches/Charleston-SC_19420704.aspx

14 Robert Dallek, An Unfinished Life John F Kennedy 1917-1963, Little, Brown and Company. New York, 2003. p 82ff.