Cultural Implications of Post-1970 Art:

The End of the Enlightenment?

By Bradford R. Collins, Ph. D.

By Bradford R. Collins, Ph. D.

— Marshal McLuhan

At our 50th class reunion in 2014, I spoke about the profound changes in the visual arts that have occurred since we graduated and what those changes tell us about shifts in Western culture. This subject bears directly on the central issue of President Kennedy’s convocation address at the groundbreaking ceremony for the Robert Frost Library in 1963. In his speech Kennedy compared Frost’s skepticism about “projects for human improvement” with his own more sanguine view. Using a classical rhetorical device, anaphora, Kennedy made a series of projections on the future of America and the world, each of which began with the phrase, “I look forward to…” Kennedy expressed more than a personal conviction; he articulated the fundamental Enlightenment optimism that characterized the modern era up to that point. Although the eighteenth century carries the label of “the Enlightenment,” that timeframe more accurately extends into the modern era, when the hopeful convictions about “man” and “his future” that developed in the eighteenth century became widely integrated into our collective thinking.

When Kennedy spoke at Amherst, this optimism was about to be tested by the seismic events of the 1960s, beginning with the assassination of the president himself. Those events raised serious doubt about the Enlightenment project and its prospects. The arts, particularly the visual arts, reflected the growing doubt. The changes in the arts and their implications can be properly understood only in the larger context of the relationship between the Enlightenment and modern art. Given the space allotted me, this will necessarily involve my painting with a broad brush, but one can often see more from a wide perspective than from focusing on details and specifics. The panoramic view of Western art since the mid-1960s suggests a crisis of cultural values with potentially epochal dimensions; Kennedy’s projections and the feelings they stirred in us in 1963 may now belong to another time.

The Enlightenment was the culmination of efforts begun by Renaissance Humanists, who turned away from medieval dogma

and sought to better understand nature and mankind through reason and empiricism. In political and economic thought, the changes that began slowly took on increased volume and velocity from the late seventeenth century to the end of the eighteenth. The growing number of so-called philosophes, or practical philosophers, and their supporters did not agree on all matters, but what emerged from their debates was a new worldview concerning humans and their institutions. The consensus held that humans were rational and essentially good, which meant that they could be allowed their freedom. The most revolutionary element of the new worldview was the claim that the ultimate purpose of the individual life was not service to God or the State but to oneself. It naturally followed that the purpose of government was to serve its subjects. The result of this conceptual revolution was the pair of political revolutions that inaugurated the Modern era, the American in 1776 and the French in 1789.

PROGRESS

These Enlightenment ideas about humanity developed in a synergistic relationship with the Scientific Revolution. In fact, the socio-political optimism of Enlightenment thinkers was ultimately grounded in the Scientific Revolution of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. As the growth of science demonstrated, nature operates by laws that are amenable to human understanding. What really excited the philosophes was the corollary: through understanding nature, humans can learn to control it for our collective betterment. In short, through the power of reason humans can arrive at truths that will enable us to improve the quality of our lives. The result was twofold: first, the Industrial Revolution and somewhat later, the new human social sciences, such as psychology and sociology. The essence of this new worldview can be encapsulated in a single word: progress, the idea that human history will henceforth be the story of the gradual improvement in human existence, producing, in the words of Immanuel Kant, “Mankind’s final coming of Age.”

Even the horrors of the Civil War, the Great Depression of the 1930s, and the two world wars did little to shake Americans’ fundamental optimism about human progress. As a result, there is little in American art before about 1970 to contradict it. Our landscape and figure paintings from the nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century constantly affirm the goodness of both nature and humanity. Much of our national art also celebrates scientific advancement and human ingenuity. Winslow Homer’s The Life Line (1884) provides a nice example. Homer depicted a woman being rescued from a sinking ship via a newly developed device called a breeches buoy, a kind of zip line set up from ship to shore that can be automatically adjusted to changes in the former’s movements. Homer covered the face of the male rescuer with the woman’s scarf in order not to detract from the true hero of the piece, the breeches buoy, and its implications concerning the ability of humans to solve their problems.

Homer: Life Line

Homer: Life Line Goya: Saturn Devouring His Children

Goya: Saturn Devouring His ChildrenThe impact of these events on early Enlightenment artists is most clearly seen in the work of the great Spanish Romantic, Francisco Goya. A member of a circle of Enlightenment advocates in Madrid at the end of the eighteenth century, Goya created a series of eighty aquatints and etchings published for public consumption in 1799 as Los Caprichos. His survey of the various superstitions and follies of contemporary Spanish society illustrated the monsters produced when Reason sleeps.

Although Goya’s hopes for awakening Reason survived the horrors of the Peninsular War (1807-14), they were completely quashed when Ferdinand VII became king in 1814. Ferdinand immediately revoked the constitution and reinstituted the Inquisition, one of Goya’s chief targets in Los Caprichos.

Goya most fully expressed his complete disillusionment with Enlightenment optimism in the utterly pessimistic scenes of the “Black Paintings” that he produced on the walls of his house in the early 1820s. [See: Francisco Goya, Saturn Devouring His Children (c. 1820)

Elsewhere in Europe doubts about Enlightenment assumptions were best expressed in the popular theme of the storm-tossed boat, a metaphor for the uncertainty of our individual and collective future. The most famous examples are probably Théodore Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa (1818-19) and J. M. W. Turner’s The Slave Ship (1840) .

The latter painting was inspired by an actual incident in which the opportunistic captain of a slave ship headed into a typhoon threw his diseased and dying cargo overboard in hopes of collecting insurance, since only slaves lost at sea because of a storm qualified for reimbursement. The work not only contradicted the Enlightenment conviction that humans are basically good, but also the notion that nature was reasonable and benign.

Gericault: Raft of the Medusa

Gericault: Raft of the Medusa Turner: The Slave Ship

Turner: The Slave ShipBy mid-century skeptical voices had been largely quieted as a result of progressive developments, which included not only the steady abolishment of slavery from country to country but also, and more importantly, advances in science and industry as featured in the newly fashionable world’s fairs.

The most conspicuous of these developments was undoubtedly the rapid growth of railways. Before the invention of the airplane in the early twentieth century, the railroad was the foremost symbol for progress, both industrial and social. Trains were featured in countless paintings of the mid to late century, both in the US and Europe, including a series by Claude Monet in 1877 dedicated to the railway yard at the Gare Saint-Lazare in Paris. [See: Claude Monet, La Gare Saint-Lazare (1877)]

Monet: La Gare

Monet: La Gare

The fullest artistic expression of Enlightenment faith, however, was in the period of modern art that historians refer to as the Modernist era or the Age of the Avant-Garde, which dates from roughly 1880 to 1970. A military term for the elite guard who lead the way for the regular troops, avant-garde was first applied to artists by Henri de Saint-Simon, a utopian socialist, in his 1825 book Opinions Littéraires, philosophiques et industrielles. In a conversation between an industrialist, an economist, and an artist, the latter declares that “We, the artists, will serve as the avant-garde. […] When we wish to spread new ideas amongst men…we inscribe those ideas on marble or canvas.”

A number of mid-century French artists, Gustave Courbet most notably, embraced the idea of the artist as political activist. The failure of the worker’s Revolution of 1848 undermined both the prospect of socialism and the avant-garde idea of the activist artist for the following generation. Thus, Eduard Manet and the Impressionists took an apolitical approach to their work.

When avant-gardism was re-embraced by some of those grouped under the label of Post-Impressionism—a catchall term for those who came through Impressionism and went their separate ways—the idea took on new meaning. Most importantly, it referred to artistic advancement, to the idea that art was evolving in a particular direction or “the mainstream.” The avant-garde were those who lead the way, who took the next step in that development. It was this new idea, and the corollary that if an artist wanted to be taken seriously by critics and historians he should produce something “advanced,” which drove the mind-boggling changes in modern art in the ensuing years.

In the work of many of these artists, the idea of artistic advancement was tied to and combined with the idea of promoting social progress. But unlike Courbet and the original avant-garde, the new breed sought to promote their own social agendas. Georges Seurat and his iconic painting, Sunday Afternoon on the Island of the Grande Jatte (1884-86) provide the classic example. Seurat called himself a Neo-Impressionist, by which he meant that his work offered a new and improved version of what Monet and company were producing in terms of both method and function. Whereas the Impressionists produced quick, immediate records of the world as seen, Seurat approached his painting more scientifically, both in the use of color complements intended to combine in the eye for a heightened approximation of natural light and in terms of emotional expression. Seurat posited that upward moving lines—like the shoreline in The

Serat: Sunday on La Grande Jatte

Serat: Sunday on La Grande JatteGrande Jatte—in combination with colors that are bright and warm elicit a happy emotional response in the viewer. And instead of merely pleasing his audience, Seurat meant to inspire them with a vision of a more evolved and civilized society. The key to the painting is the contrast between the restrained behavior of the people, particularly the little girl in white at center, and the unrestrained play of the unruly dogs in black at the bottom. In effect, Seurat was showing us the next step in the human evolutionary process that began with monkeys, which is why he included one in the painting.

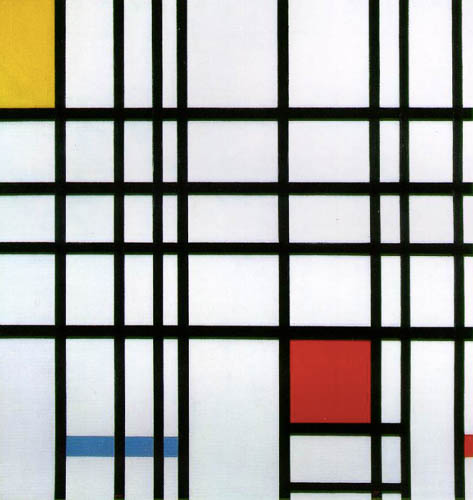

Another Post-Impressionist, Paul Cezanne also wanted to produce an improved version of Impressionism, although his was a purely artistic endeavor without social or political thrust. In contrast to Monet’s purely phenomenological approach to nature, Cezanne wanted to record the fact of its stability and solidity, as well. That he did so in an increasingly abstract style in his late paintings of Mont Sainte-Victoire [See: Paul Cezanne, Mont Saint-Victoire (1906)] inspired Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque [See: [See: Pablo Picasso, Ma Jolie (1911-12)] to develop the first non-representational art form in their Analytical Cubist works of 1911-12. These paintings in turn inspired a whole generation of European artists to either take liberties with representational forms, like the Italian Futurists, or abandon them completely, as in the case of Piet Mondrian or the Russian Constructivists. [See: Piet Mondrian, Composition with Red, Blue, and Yellow (1930)

Cezanne: Mont St Victoire

Cezanne: Mont St Victoire Picasso - Ma Jolie

Picasso - Ma JolieUnlike the Cubists, the Italian Futurists and the Russian Constructivists had clearly defined Utopian goals. On the basis of the aesthetic principles he developed in his art, Mondrian wished to redesign “everything that exists.” He held a naïve belief that environment alone determines psychology, and that harmonious surroundings would produce harmonious people and societies. Constructivists such as Naum Gabo [See: Naum Gabo, Column (1921)], on the other hand, believed that art was “contagious.” Their engineere d art would produce the constructive geniuses who would help create the new Communist Utopia.

Mondrian: Composition

Mondrian: Composition Gabo: Column

Gabo: Column Van Gogh: Starry Night

Van Gogh: Starry NightSeurat’s work instigated the rationalist, anti-intuitive strain of Modernist art that reached its apogee before WW II in the work of Mondrian and the Russians, but it also contributed importantly to the counter-strain that emphasized emotion and intuition. Seurat’s use of color for expressive purpose was the starting point for Vincent van Gogh’s preoccupation with color. [See: Vincent van Gogh, Starry Night (1889)]

During the last year of his life, van Gogh came to use color expressionistically, not to characterize his subjects but to record the purely personal feelings he brought to them. Van Gogh’s work touched off the expressionist wave of avant-garde art that swept Europe in the years before WW I in Fauvism, The Bridge, and The Blue Rider movements, most famously. In the years between the two wars, this current was continued by the Dadaist and culminated in Surrealism, which sought the complete liberation of the Id.

Surrealist art came in two forms, the regressive representational style of Salvador Dali and the freely expressive automatist brand practiced by most members of the group, such as Joan Miro and André Masson. [See: André Masson, Battle of the Fishes (1926)

It was out of this latter side of the movement that American Abstract Expressionism emerged in the post-war period. Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning and their colleagues were the first Americans to be recognized as leaders of the avant-garde, thereby shifting the center of the art world from Paris to New York. [See: Willem de Kooning, Police Gazette (1955)]

Masson: Battle of the Fishes

Masson: Battle of the Fishes Koenig: Police Gazette

Koenig: Police GazetteConsciously steered by the critic Clement Greenberg and his followers, Abstract Expressionism “naturally” evolved into Post-Painterly Abstraction at the end of the 1950s and then to Minimalist painting and sculpture in the 1960s. The decade witnessed other developments as well, of course—the Neo-Dada productions of Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg that opened the way for Pop Art, most notably— but according to the reigning Greenbergians, these were merely “fads,” historical cul-de-sacs with no relation to the “mainstream” development of Modernist art, which meant that they could be ignored.

But it was Minimalism, not Neo-Dada or Pop that turned out to be the dead end, the movement that marked the end of Modernism. The decade of the 1970s was quickly dubbed the Post-Minimalist era. A profusion of different kinds of art emerged in that decade in reaction to Minimalism, often using its formal means but for radically different ends. In the 70s, we saw the first signs of the pluralism that now characterizes contemporary art.

Instead of movements and all that they imply about historical development, we now have tendencies and groupings. Indeed, most of these are more for the art historian’s convenience than an indication of collective aims. The YBAs, for example, have little in common except for the fact that they are all young, British, and artists!

The new radical pluralism was the first indication that the art world had lost faith in the avant-garde concept and its corollary, an artistic mainstream, which had driven production for nearly a century. Although the term “avant-garde” is still in use, it now simply refers to something new or different, not to something historically “advanced” or better.

What collapsed, in fact, was the Enlightenment idea of historical progress. The events of the 1960s and early 1970s had put historical progress, the meta-narrative that had underpinned avant-gardism, in doubt. The assassinations of John F. Kennedy, Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King, the Vietnam War, the failure of May 1968 and other student-led initiatives on the continent, and most importantly the growing awareness that the Industrial Revolution had led to profound ecological disturbances threatening the viability of life on the planet, collectively rendered the idea of progress dubious. The utter failure of world leaders to deal effectively with the existential crisis of climate change and a host of social problems has only confirmed and deepened those doubts.

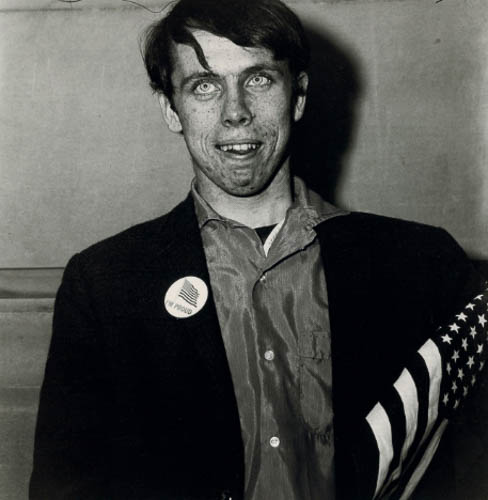

To be sure, one can still find beauty, especially in photography, but much of this is either manipulated and thus offered as mere imagery, or exceptional moments stolen from an otherwise defective world. More importantly, since Diane Arbus [See: Diane Arbus, Patriotic Young Man with Flag (1967) and Lee Friedlander [See: Lee Friedlander, New York City (1963)] emerged in the late 1960s most art photography has been devoted to images of social chaos, human degradation, or physical imperfection, as in the work of Raghubir Singh [See: Raghubir Singh, Mango Season, Crawford Market, Mumbai (1993)], Nan Goldin [See: Nan Goldin, Nan One Month After Being Battered (1984), and Rineke Dijkstra [See: Rineke Dijkstra, Julie (1994)], respectively.

Arbus: Patriotic Young Man

Arbus: Patriotic Young Man Friedlander: NYC

Friedlander: NYC Singh: Mango Season

Singh: Mango Season Golden: One Month

Golden: One MonthThe “artist activist” has not disappeared. An internet search of the term will turn up the names of dozens of artists dedicated to the prospect of human betterment. The super-realist sculpture of Duane Hanson [See: Duane Hanson, Supermarket Shopper (1970)], the installations of Ai Weiwie [See: Ai Weiwei, Refugees Through the Eyes of Celebrities (2016)] and the graffiti of Banksy [See: Banksy, Balloons (Palestine, 2005)], all document our current imperfections with the hope that we might reform them.

Dijkatra: Julie

Dijkatra: Julie Hanson: Supermarket Shopper

Hanson: Supermarket Shopper Weiwei: Refuges

Weiwei: Refuges Banksy: Balloons

Banksy: BalloonsBut “telling truth to power,” to rephrase Kennedy, is only meaningful if those being addressed are responsive. The current consensus is that these artistic voices, however admirable their intentions, are being heard only by the proverbial choir: that Hanson has had no more effect on American culture than Ai Weiwei has had on the Chinese government or Banksy on those responsible for the Palestinian situation. Which is to say that contemporary art seems to offer no match for our current problems.

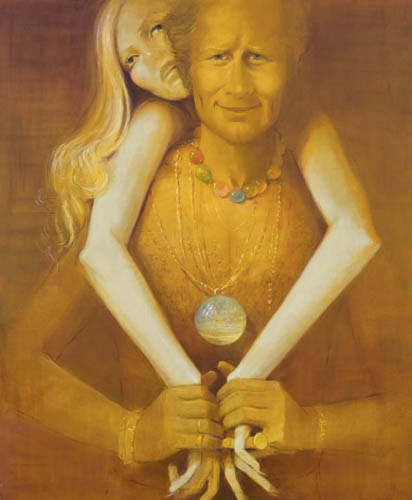

The vast majority of the recent depictions of human imperfection are offered simply as true, without expectations. This testimony comes in two main varieties. The first—found in the work of John Currin [See: John Currin, Sinister Overtones: Park City Grill (2000)], Charles Ray [See: Charles Ray, Family Romance (1993)], Lisa Yuskavage [See: Lisa Yuskavage, Bad Habits (1996)], and Rachel Harrison [See: Rachel Harrison, I’m with Stupid (2007)] —is presented for our amusement, as farce, scenes from the human comedy. Such work falls under the rubric of Endgame, a term borrowed from chess to describe the point in the contest when defeat is clear but one still has a few moves left.

Currin: Newspaper Couple

Currin: Newspaper Couple Ray: Family Romance

Ray: Family Romance Luskavage: PM

Luskavage: PM Harrison: With Stupid

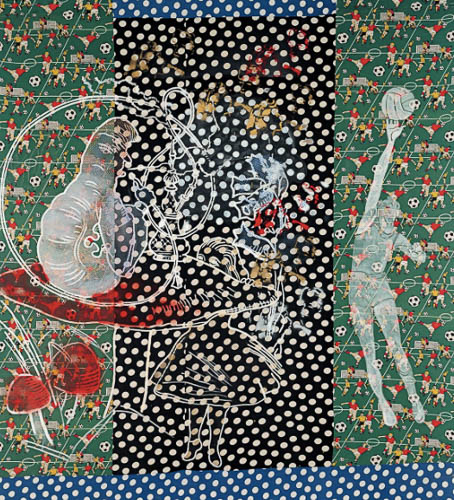

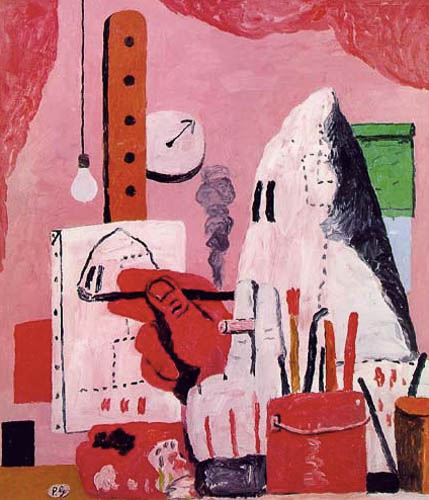

Harrison: With StupidStrategically, these are artists making the best of a bad situation. Jeff Koons’s highly crafted kitsch [See: Jeff Koons, Balloon Dog (1994-2000)] and Sigmar Polke’s decorative approach [See: Sigmar Polk, Alice in Wonderland (1972)] to the chaotic flood of contemporary imagery might also belong under this broad umbrella. The second variety includes the work of Philip Guston [Philip Guston, The Studio (1969)], Lucian Freud [Lucian Freud, Painter Working: Reflection (1993)], ….

Koons: Balloon Dog

Koons: Balloon Dog Polke: Alice in Wonderland

Polke: Alice in Wonderland Guston: The Studio

Guston: The Studio Freund: Self-Portrait

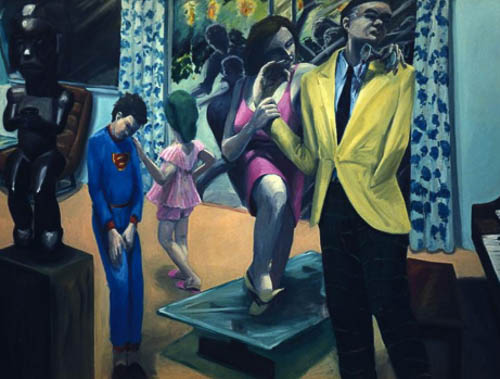

Freund: Self-Portrait… Mike Kelly [Mike Kelly, Frankenstein (1989)], Kiki Smith [Kiki Smith, Tale (1992)], Eric Fischl [Eric Fischl, Time for Bed (1981)] , David Salle [David Salle, Miner (1985)]

Kelley: Frankenstein

Kelley: Frankenstein Smith: Seer

Smith: Seer Fischl: Time for Bed

Fischl: Time for Bed Salle: Miner

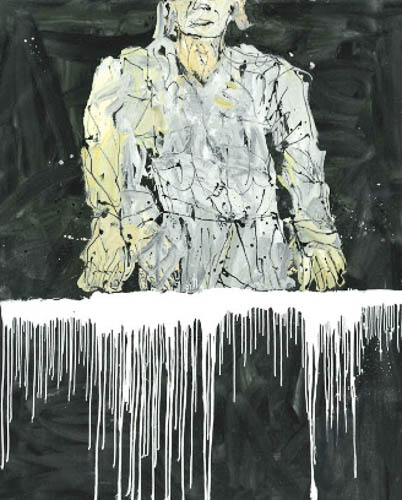

Salle: Miner…, Georg Baselitz [Georg Baselitz, Good Grey (2009)], and Paul McCarthy [Paul McCarthy, Santa Chocolat Shop (detail of a performance, 1997)]

Baselitz: Good Grey

Baselitz: Good Grey McCarthy: Art

McCarthy: ArtTheir work, to varying degrees, is dispiriting and/or depressing. In the work of these artists, and the photographers mentioned above, the Utopian optimism of the Enlightenment has given way to dystopian fears.

Whether the skeptical and pessimistic currents of post-1970 visual art toll the end of the Enlightenment or just the latest crisis of Enlightenment faith will depend on the larger culture. Can we marshal our reason, decency, and common sense to pull out of our current cultural tailspin? Kennedy and the philosophes are holding their collective breath.